Water is a life-sustaining resource, and yet some do not have equitable or sufficient access to it in the Colorado River Basin. As climate change and drought threaten water accessibility in the West, there are calls to review the status quo. For many, the Colorado River Compact is an imperfect approach to allocating the river’s water. It is economically inefficient, over-appropriated by some water users, and exclusionary for others. Economists, like Ellen Bruno, contend that an interstate water trading program could potentially solve these problems.

The Colorado River Compact

A water allocation is the authority to take a pre-established amount of water from its source within a designated timeframe. As one can imagine, the allocations for the Colorado River’s water have a complicated history.

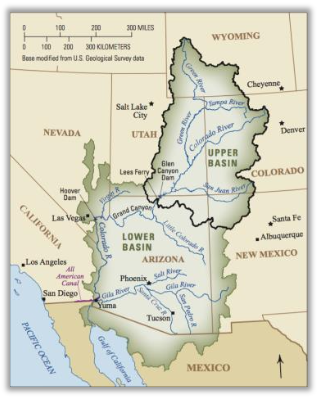

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 is a legal agreement between the seven states in the Colorado River Basin. This interstate compact governs water allocations by dividing the water equally between the “Upper” and “Lower” basins (Figure 1). Thus, each basin has 7.5 million-acre feet of water. The compact further divides water allocations between the states that fall within each respective basin. For example, water allocations for the Upper Basin go to Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

Three Key Pitfalls

The Colorado River Compact was a reasonable solution to water allocation disputes in 1922; however, there are three outstanding issues with the compact today.

First, the allocations fixed in 1922 were appropriate for water use patterns at the time. Unfortunately, the demand for water in the West has changed over the past 96 years. New demographic and economic changes confirm the need for the agreement to evolve simultaneously with development.

Second, flows from the Colorado River were overestimated at the time of the compact. This caused some allocations to be too generous, while others are insufficient.

Third, Native American tribes were excluded from the compact. They did not receive any allocations even though they have federally recognized water rights.

Economists Favor Efficiency

As the world tackles problem-solving for scarce resources, economists share an essential rule: efficiency.

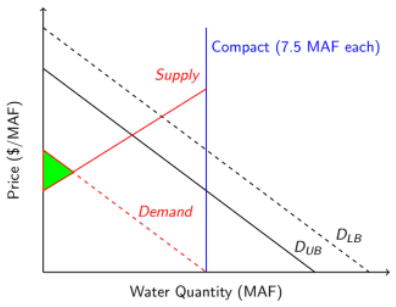

In terms of the Colorado River’s water, an allocative efficiency would entail a situation in which no water user could be made better off with a different allocation without making another user worse off. A water trading regime would meet these criteria because there exists a price point in which a water seller could successfully conduct business with a water buyer. For the Colorado River Basin, the Upper Basin states would be the sellers due to their larger water supply, and the Lower Basin states would be the buyers due to their increased demand for water (Figure 2).

Criteria for a Water Trading Program

A water reallocation scheme should meet several criteria to have success within the Colorado River Basin. First, there should be flexibility in the allocation of existing water supplies. Water users with tenure should have assurance that they will continue to have access to their water in the future as trading will be voluntary. This will increase confidence in the market, and individual users will face the full cost of water. The outcomes of any trading agreements should have predictable outcome processes. Finally, all participating water users should view the program as equitable.

Challenges of Program Implementation

An interstate trading program would require extensive social marketing and trade reconstruction. The program would need full buy-in from all states within the Colorado River Basin, which would include the development of an interstate governing body. Current intrastate markets would need to be standardized and consolidated. Social marketing would try to shift perceptions of unfairness and distrust within disenfranchised communities. Finally, program administrators should prepare for any unintended impacts on third parties.

The Case for Interstate Water Trading

Bruno and other economists favor a voluntary, interstate water trading program because it could efficiently reallocate resources within the compact and yield economic benefits. Some purport that the benefits could be as high as $140 million per year.

A program with an annual review could accommodate changes in the demand for water caused by demographic and economic shifts. This flexibility could meet the needs of users over time. Another benefit to a trading regime is that the federal government could participate as a buyer. It could then purchase water on behalf of users in the Colorado River Basin who either have insufficient allocations from the compact or who were completely excluded from the compact.

The Colorado River Compact is not ideal, and an interstate water trading program holds the promise of improved water management through reallocations and pricing. As drought and climate change continue to threaten scare resources, policy should adapt and incorporate this innovative idea as one solution.