Our research expedition traveled 280 miles from the snowy peaks of the of the Wrangle St. Elias Range to the salty air of the Copper River Delta in search of science. On our journey from the Kennicott Glacier to the Delta we looked for many things, and moose were one of them. According to the theoretical Copper River Watershed moose occupation model, we expected to find many moose (or evidence thereof) in the interior portion (north of the Chugach Mountains) of our trip, no moose in the Copper River Canyon (the section where the Copper River dissects the Chugach Mountains), and then plenty of moose again south of the Chugach Mountains and down to the Copper River Delta. This occupation model originates from the suggestion that the Copper River Canyon acts as a migration barrier preventing moose from moving downstream in the Copper River Watershed from the interior where they are abundant to the Delta where they did not initially colonize. However, beginning in 1949 moose were introduced to the Delta region where they persist successfully yielding the above described occupation model (see Hammersmark 2002 (pdf) for more details).

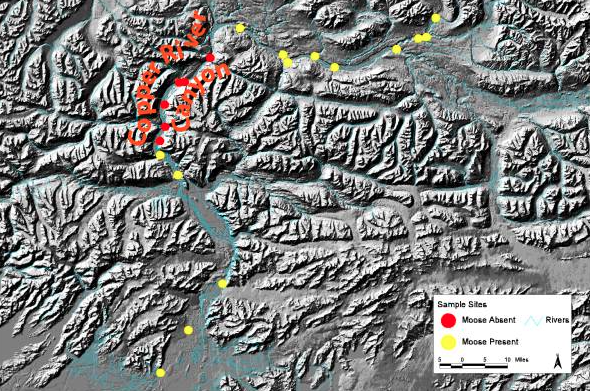

While actual moose sitings were limited, the evidence of their recent presence was not. At several points along the journey, moose tracks, scat, and evidence of browsing were observed and noted. On three occasions actual moose were observed: one dead moose (soon to be labeled LMD: Large Moosey Debris) in the Chitna River at the Confluence Camp, two moose observed again in the Chitna River swimming through Moose Narrows (described below), and one grazing in a wetland in the Copper River Delta after the take-out of the float trip. The map below shows sampling locations and whether moose evidence was observed. The color of the symbol at each location indicates the presence (yellow) or absence (red) of moose at the sampling site.

On our fifth evening on the river while camping at the soon to be named “Moose Narrows Camp,” some colleagues and I were sampling some of the midnight sun. To our delight, at around 11 pm two moose (or should I say meese?), a cow and her calf were observed in the river, swimming, and headed downstream in a hurry. Members of the trip speculated as to the reason why they were in the water (trying to cross the river, accidental swim by the calf with the mother following, transportation, etc), but regardless, they were in the river and swimming. Moose are known to be good swimmers, but I had previously only observed them swimming in still water environments, and somehow I never imagined them in swift rivers headed downstream at 10 mph. The cow and calf became separated when the calf eddied out and the mother continued downstream. Despite the efforts of the mother, the two were never observed to reunite. Further details of this heart-wrenching saga have been saved for an upcoming episode of Wild America.

Upon telling the others of the siting, discussions immediately arose regarding the Copper River Canyon acting as a migration barrier to moose. With the magnificent swimming skills that we had observed, surly moose could make it beyond the canyon to the awaiting willow rich oasis of the delta. If swimming through the Chugach Mountains was too much, then surly the corridor could be walked during the winter, when the flow in the Copper River diminishes considerably and snowmobiles travel along the river corridor. The jury seemed unconvinced of the ability of the Copper River Canyon to act as a barrier to these Olympic class swimmers and runners.

Soon our flow path down the Chitna River merged with the Copper River and headed south through the Chugach Mountains in the Copper River Canyon, and evidence of moose occupation ceased. No tracks, no scat, no evidence of browsing, no moose! They just didn’t seem to be there. This fit the model, but why? The willow rich, bar and floodplain setting of the upper watershed had vanished leaving steep canyon walls covered in alder forests, which extended right down to the river’s edge. As far as moose are concerned, the Copper River Canyon is not a hospitable place. Moose really like willows but are not so fond of alders. With no abundant geomorphic features for willows to grow upon, the moose have no reason to head downstream.

As the walls of the canyon pulled away and floodplain areas covered in willows and herbaceous species emerged, evidence of moose occupation again appeared. We had exited the Copper River Canyon, and were again in moose country. Sadly eleven days later our journey in search of moose, among other things ended. We drove off to Cordova to catch a ferry, but first to our delight we spotted a moose browsing in a wetland, undoubtedly an ancestor of a planted moose. The model was right, moose in the interior and in the delta (by the hand of man), but not in the canyon. What a terrific display of the role of biotic, abiotic and anthropogenic elements in controlling the ecology of the Copper River Watershed.